Who Said That Art Dies When It Is Bought

I t's always tempting to mythologise the dead, especially those who die young and beautiful. And if the expressionless person is also astonishingly gifted, and then the myth becomes inevitable. Jean-Michel Basquiat was just 27 when he died, in 1988, a strikingly gorgeous fellow whose stunning, genre-wrecking piece of work had already brought him to international attending; who had in the space of just a few years morphed from an undercover graffiti creative person into a painter who allowable many thousands of dollars for his canvases.

So perhaps I shouldn't exist surprised that everyone I talk to who knew Basquiat when he was alive, from girlfriends to collectors, musicians to painters, speaks about him as special. Still, it's noticeable that they all practice. Basquiat – even before he was acknowledged as an creative person – was seen by his friends as exceptional.

"I knew when I met him that he was beyond the normal," says musician and film-maker Michael Holman, who founded the racket band Gray with Basquiat. "Jean-Michel had his faults, he was mischievous, he had sure things near him that could exist chosen amoral, just setting that aside, he had something that I'1000 sure he had from the moment he was born. It was like he was born fully realised, a realised beingness."

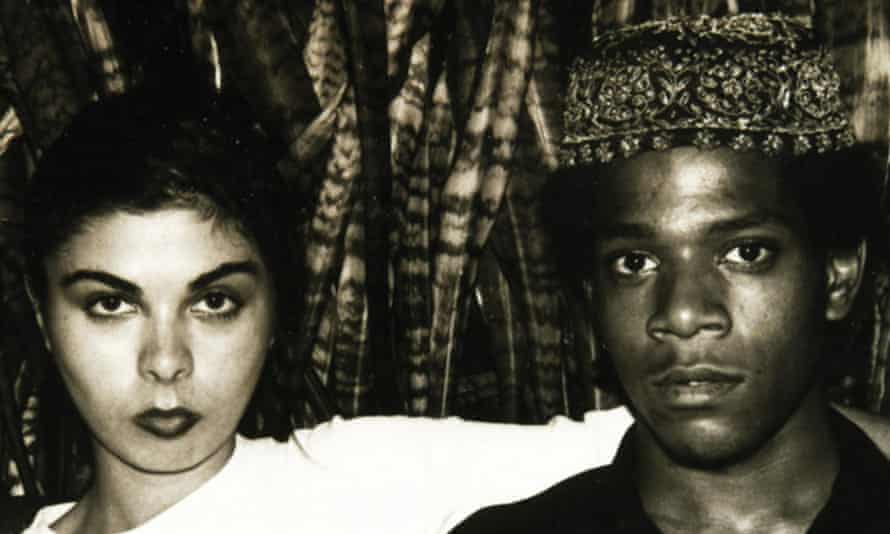

"He was a cute person and an amazing artist," says Alexis Adler, a former girlfriend. "I recognised that from the become-go. I knew he was brilliant. The only person around that time I felt the same thing about was Madonna. I totally, 100% knew they were going to exist large."

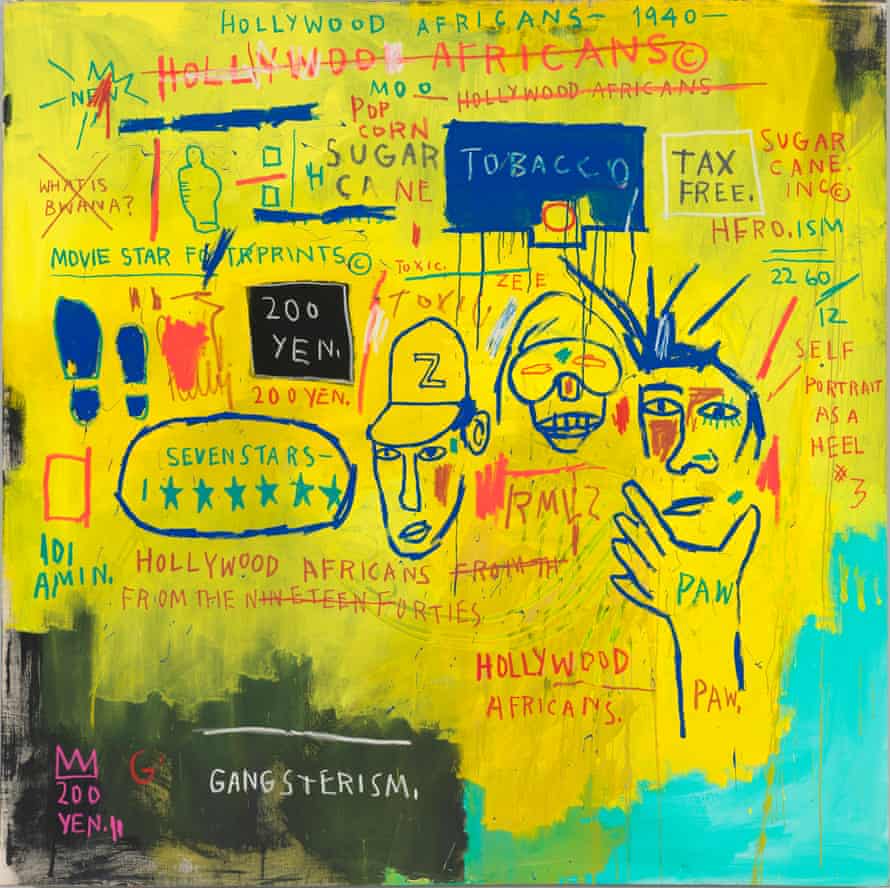

Basquiat the human and Basquiat the painter are hard to untangle. He lived hard and died harder (from an unintentional heroin overdose), and had more of the rock-star persona than the art aesthete about him, a cool celebrity sparkle that didn't ever work in his favour. Some art connoisseurs find his piece of work difficult to take seriously; others, though, accept an firsthand, nigh visceral response. To me, a non-art critic, his work is fantastic: it feels contemporary, with a cluttered, musical sensibility. It'southward cute and hectic, immature and old, graphic, arresting, packed with cryptic codes; in that location's a questioning of identity, specially race, and a sampling of life'south stimuli that takes in music, cartoons, commerce and institutions, equally well as celebrities and art greats. (Not sex, though: though he had lots of partners, his paintings are rarely erotic.). You could stand in front of a Basquiat painting and be fascinated for hours.

Since he died, Basquiat has had a mixed reputation. At that place was a time in the 1990s when he was dismissed equally a lightweight. Museums rejected him every bit a jumped-up wall-sprayer. But over the by few years, his star has been on the rise and fifty-fifty those who are snooty about his art can't argue with his cultural influence. A few years ago a Christie's spokesperson described him, pointedly, as "the most collected creative person of sportsmen, actors, musicians and entrepreneurs". As ane of the few blackness American painters to break through into international consciousness, he is referenced a lot in hip-hop: Kanye Due west, Jay-Z, Swizz Beatz, Nas and others cite Basquiat in their lyrics; Jay-Z, in Most Kingz, uses the "most kings get their head cut off" phrase from Basquiat's painting Charles the Get-go. Jay-Z and Swizz Beatz ain his works, as practice Johnny Depp, John McEnroe and Leonardo DiCaprio. Debbie Harry was the start person ever to pay for a Basquiat slice; Madonna owns his fine art and they dated for a couple of months in the mid-80s.

A household proper noun in the US, Basquiat is less well known in the UK, though the sale, in May, of one of his paintings (Untitled (LA Painting), 1982) for $110.5m (£85m), the highest amount ever for an American artist at auction, made headlines. Now, Boom for Real, a vast exhibition at the Barbican – the first Basquiat prove in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland for more than 20 years – aims to open our eyes. Researched and curated for four years, it follows his career from street to gallery, acknowledges the infrequent times he was working in, and expands its references from straightforwardly visual art to music, literature, Boob tube and movies, all areas in which Basquiat experimented. It tries to run across things from Basquiat's point of view.

Eleanor Nairne, co-curator of the show, explains why there hasn't been a full retrospective until at present. Although Basquiat was immensely prolific during his short life, institutions were slow to recognise his talent. "The time betwixt his showtime solo testify and his expiry was six years," she says. "Institutions do not move that apace. During his lifetime he only had ii shows in a public space [as opposed to a commercial gallery]. At that place's non a single work in a public collection in the UK." There are non many in the US, either: the Whitney Museum of American Fine art in New York has a couple, but when the metropolis'due south Museum of Modernistic Art (MoMA) was offered his work when he was alive, it said no, and it still doesn't own any of his paintings (it has some on loan). The head curator, Ann Temkin, later admitted that Basquiat's work was too advanced for her when she was offered it. "I didn't recognise information technology as peachy, it didn't await like anything I knew."

Basquiat was born to a eye-class family in Brooklyn. His begetter was Haitian – quite a strict figure – and his mother, whose parents were Puerto Rican, was born in Brooklyn. His parents separate up when he was seven and he and his sisters lived with his father, including a move, for a while, to Puerto Rico. His mother, to whom he was close, was committed to a mental hospital when he was 11. Basquiat was rebellious, angry, and moved from school to school. His education ended in New York when, for a dare, he emptied a box of shaving foam over the principal'southward head during a graduation ceremony. Past xv, he was leaving home on and off. He once slept in Washington Square Park for a week.

New York Metropolis in the tardily 1970s was utterly unlike it is at present: united nations-glitzy, rough, with many buildings burnt out and abandoned. "The city was aging," says Alexis Adler, "but it was a very gratuitous time. We were able to do whatever we wanted considering nobody cared." Rents were cheap (or people squatted) and downtown New York was a grubby, exhilarating mecca for the artistic dispossessed. The punk scene, centred on the venue CBGB, was giving way to something more experimental, involving art, picture show and what would become hip-hop. Everyone went out every night, everyone was creative, everyone was going to make it large.

"We were all these young kids in New York to carry out our Warhol fantasy," says Michael Holman, "only instead of being a ringleader as Warhol was, we were in the band ourselves, making fine art ourselves, nosotros were acting in films, making films, we were all one-man shows, with a lot of collaborations. That was the norm, to be a polymath. Whether y'all were a painter, an actor, a poet… you also had to exist in a band, in order to really be cool."

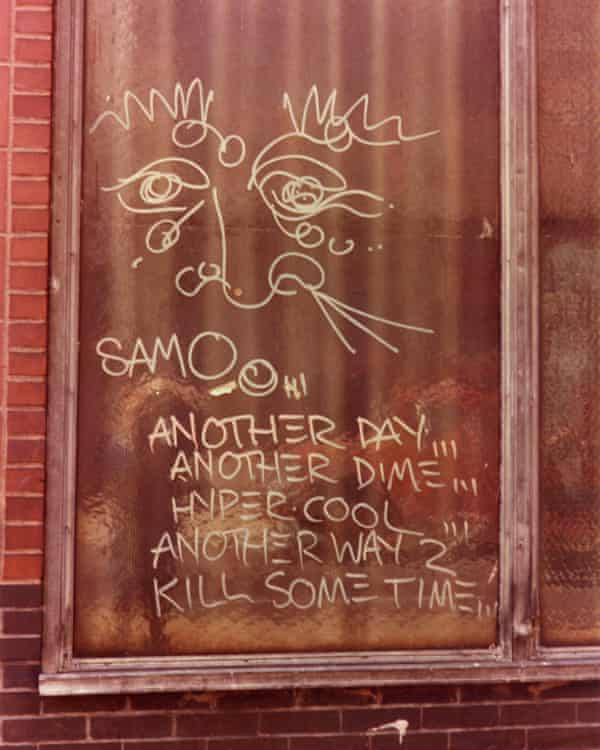

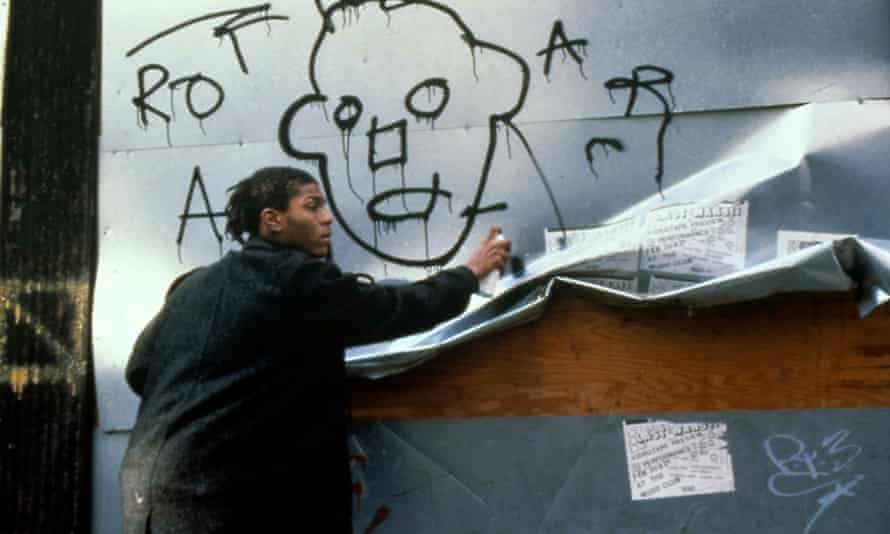

Basquiat was, of class, in a band, with Holman and others including Vincent Gallo; they were called Gray. They formed in 1979, but before that, Basquiat made his presence felt through his graffiti. Working with his school friend Al Diaz, from 1978 he was spraying the buildings of downtown NYC with their shared SAMO tag. SAMO©, originally a cartoon character Basquiat had fatigued for a school mag, was derived from the phrase "same former shit". It was meant, in part, to be a satire on corporations and the tag was straightforward, not decorative. Instead of pictures, SAMO© asked odd questions, or made enigmatic, poetic declarations: "SAMO© AS A CONGLOMERATE OF Fallow-GENIOUS [sic]" or "PAY FOR SOUP, BUILD A FORT, Set up THAT ON FIRE". The SAMO© tag was everywhere. Earlier anyone knew Jean-Michel Basquiat, they knew SAMO©.

Basquiat left dwelling house permanently at 16 and slept on the sofas and floors of friends' places, including UK artist Stan Peskett'south Canal Street loft. There he made friends with graffiti artists including Fred Brathwaite (better known as Fab v Freddy) and Lee Quiñones of graffiti grouping the Fabulous 5, and fabricated postcards and collages. (Once Basquiat spotted Andy Warhol in a eating place, popped in and sold him a couple of those postcards.) Brathwaite and Holman put on a political party at the loft on 29 Apr 1979, as a way of bringing uptown hip-hop to the downtown art crowd. Before the political party started, Holman remembers, this kid turned up, and said he wanted to be in the evidence. Holman didn't know him, but "people with that kind of free energy, you lot never stand in their way, yous just say, Yep, go!" They set up up a large piece of photo paper and Basquiat started spraying information technology with a can of red paint. He wrote: "Which of the post-obit is omniprznt [sic]? a) Lee Harvey Oswald b) Coca Cola logo c) General Melonry or d) SAMO." "And we all went, Oh my God, this is SAMO!" says Holman. Later at the party, Basquiat asked Holman, who had been in the fine art-rock band the Tubes, if he too wanted to exist in a ring. Greyness was formed there and then.

The members of Grayness, which settled into the line-upwards of Holman, Basquiat, Wayne Clifford and Nick Taylor, deliberately used painting or sculpture as references, as opposed to music. Their highest expression of praise was "ignorant", used in the same way as bad (meaning good). Holman recalls playing a gig with a long loop of record passing through a reel-to-reel machine and so around the whole band. Brathwaite was at Gray's first gig, at the Mudd Club in New York, and said later: "David Byrne [of Talking Heads] was there. Debbie Harry. It was a real who's who. Anybody was there because of Jean…SAMO's in a band! They came out and played for just x minutes. Somebody was playing in a box."

Gray ended when Basquiat'due south painting took off. He was always painting and drawing, initially in the style of Peter Max (think Yellow Submarine), but quickly plant his ain aesthetic, which used writing, and had elements of Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg. Because he had no coin for canvases, he painted on the detritus he dragged in from the street – doors, briefcases, tyres – likewise as the more permanent elements in his flat: the fridge, the TV, the wall, the floor. Nigh the same fourth dimension that Grayness began, Basquiat started dating Adler, so a budding embryologist (he stepped in to protect her when she innocently provoked a street fight). Adler found a flat – at 527 E 12th Street – where she still lives today, and they both moved in. There, Basquiat painted on everything, including Adler's clothes. (When, in 2013, Adler revealed that she had kept a lot of his work, she sold an bodily wall of her apartment via a Christies auction: it had a Basquiat painting of Olive Oyl on information technology. "They were careful about taking it out," she tells me. "And now we have glass bricks there instead!")

Although she and Basquiat were sleeping together, it wasn't a straightforward swain-girlfriend thing, says Adler. "Information technology was before Aids, a wild fourth dimension, you could have whatever human relationship yous wanted." They had separate rooms, and had sex with other people. Adler bought a camera to take pictures of Basquiat'southward art, and of him mucking near: he played with putty on his nose, was interested in movie and Goggle box (his phrase "blast for existent", used when he was impressed, came from a TV programme), and shaved the front half of his head, so he would "look as though he was coming and going at the aforementioned fourth dimension".

They went out every night to the newly opened Mudd Guild, in the Tribeca district. Friends came over until all hours (hard for Adler, who worked in a laboratory by day). PiL's Metal Box was on rotation, along with Bowie'south Low and records by Ornette Colman, Miles Davis. Adler loved Metallic Box and nailed the embrace up on the wall. When Basquiat saw it, he was total of disdain. He took the anthology down and nailed up William Burroughs'southward The Naked Luncheon in its place. "He establish it offensive that I would put it up," says Adler. It wasn't practiced enough to be art in his eyes.

Basquiat lasted at Adler's flat until the spring of 1980. During that year, his work featured in a couple of grouping shows and he played the lead function in the flick New York Beat Movie (eventually released in 2000 every bit Downtown 81; the Barbican testify will play it in full). In the film, Basquiat is the star, but it's fun to play spot-the-famous-person: there are cameos by Debbie Harry, Fab five Freddy, Lee Quiñones; the band DNA and even Kid Creole and the Coconuts brand an appearance. The plot is of the solar day-in-the-life blazon: Basquiat plays an artist who wanders the street trying to sell a painting so he can get enough money to move back into his flat. He sells it, but is paid by check, so he gild-hops, trying to find a girl he can get home with. You can't imagine the role was much of a stretch.

When he wasn't clubbing, Basquiat worked hard – Brook Bartlett, an artist he mentored in the early 1980s, recalls him painting incessantly – and his shift from being penniless to rich happened between 1981 and 1982. He was by and so living with Suzanne Mallouk, who had moved from Canada to become an artist. They'd met when she was bartending at Night Bird. Basquiat would come in, stand up at the back of the room and stare at her. Initially, she thought he was a hobo – he had shaved pilus at the front end of his head, bleached baby dreads at the back, and wore a coat five sizes too big. "He wouldn't come to the bar considering he had no coin for drinks," she recalls. "But then, subsequently two weeks, he came in, put a load of alter down and bought the most expensive beverage in the identify: Rémy Martin. $seven!". Mallouk was intrigued. They were the same age and had a lot in common. Basquiat moved into her tiny walk-up flat.

Within eight months, in that location was coin everywhere. Mallouk: "I watched him sell his first painting to Deborah Harry for $200, and then a few months later on he was selling paintings for $twenty,000 each, selling them faster than he could pigment them. I watched him make his outset 1000000. We went from stealing bread on the style habitation from the Mudd Club and eating pasta to buying groceries at Dean & DeLuca; the refrigerator was full of pastries and caviar, nosotros were drinking Cristal champagne. We were 21 years erstwhile." Basquiat would get out piles of greenbacks around the apartment, buy Armani suits past the dozen, throw parties with "hills of cocaine". His rise coincided with a shift in the city: financiers were looking to invest in art, and they were cruising around fine art shows, snapping up new work.

The showtime public showing of Basquiat's paintings was in 1981: New York/New Wave, at PS1 in Long Island, brought together by Mudd Lodge co-founder and curator Diego Cortez. It was a group bear witness that included pieces by William Burroughs, David Byrne, Keith Haring, Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol, but Basquiat was given a whole wall, which he filled with 20 paintings. (The Barbican show recreates this, with 16 of the original 20 on display.) His work caused a sensation.

Basquiat gained a dealer: Annina Nosei. She gave him the basement under her gallery to work in (Fred Brathwaite didn't approve: "A black kid, painting in the basement, it'south not adept, man", he said later), which was where Herb and Lenore Schorr, beneficial and interested art collectors, met him. The Schorrs spent some time in the gallery choosing a slice of work, without knowing that Basquiat was working beneath them. Once they'd decided, he came upwardly, and, though other collectors plant Basquiat threatening or obtuse, they liked him immediately. He didn't explicate his work – "he always said: "If you tin can't figure it out, it'southward your problem," says Lenore; to Bartlett, he said: "I paint ghosts" – simply he pointed out parts that he thought he'd done especially well, such every bit a snake.

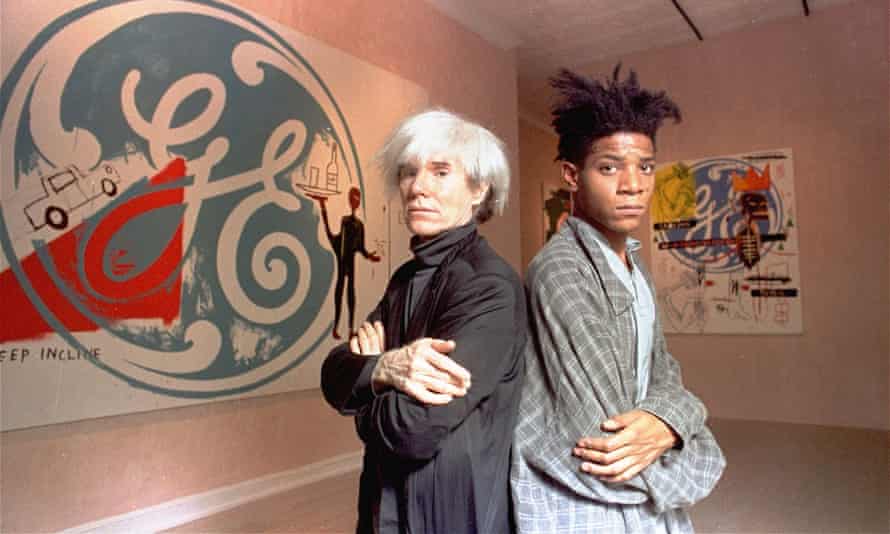

Things were on the upwardly. In early 1982, Nosei bundled for Basquiat and Mallouk to motility from their small flat to the much fancier 151 Crosby Street in Soho, and she hosted his first ever solo show at her gallery: a huge success. Through another dealer, Bruno Bischofberger (his most consistent representative), Basquiat was formally introduced to Andy Warhol; afterwards, Basquiat immediately made a painting of the 2 of them, and had it delivered to Warhol, still moisture, two hours later they'd parted. They formed the first of a friendship. Basquiat was then asked to do a evidence in LA, at the Gagosian gallery.

Motion-picture show-maker Tamra Davis, who made the Basquiat documentary Radiant Child (2009), met him in Los Angeles. She was an assistant at some other gallery and a friend brought Basquiat over. "Jean-Michel came and he didn't have a auto and he didn't know where to become and nosotros showed him around," she says. "That was our assignment. It was the funnest thing ever. I was going to pic school, and he really loved films, and so we would go to the movies together, talk about them. He was the new matter in town, anybody wanted to become to know him. He was so charming, merely it was besides similar hanging out with the Tasmanian devil. Everywhere he went, chaos would occur. Yous didn't know what was going to happen side by side. It was invigorating, just information technology was besides really tiring."

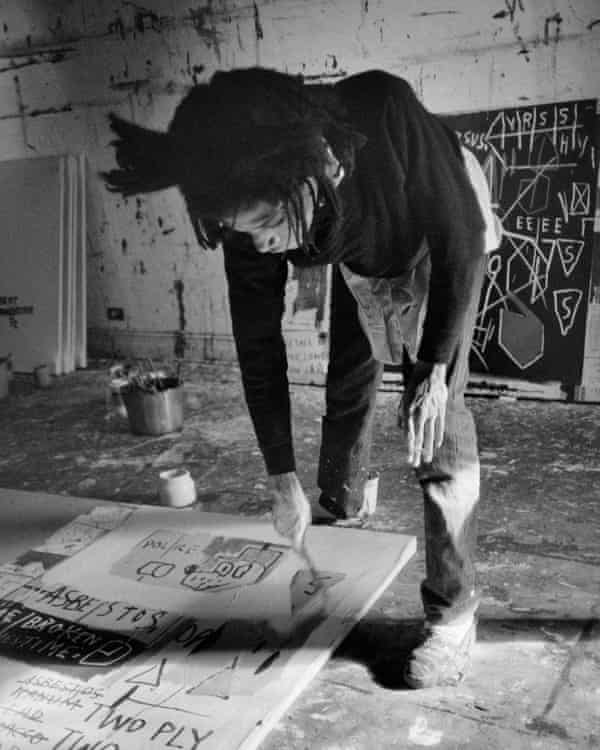

Basquiat, though, was never tired. He had unending energy, partly drug-fuelled: he needed it in LA, as he brought no paintings with him. He rarely did, for his shows: instead he'd arrive early on at whichever city the show was in and make the paintings there. "He could make 20 paintings in three weeks," says Davis. In 1986, she filmed him working: he would have source books open, the Television on, music playing and worked on several canvases at once. For this first LA show, he created works including Untitled (Yellow Tar and Feathers) and Untitled (LA Painting), the moving-picture show that just cost Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa $110.5m (in 1984, information technology went for $19,000). Every single one sold.

In one case back in New York, Basquiat left Nosei and joined another dealer, Mary Boone. His reputation was rocketing. The opening for his solo prove at Patti Astor's Fun Gallery was packed with celebrities, recall the Schorrs, who consider that particular show to exist his finest, and all the work sold on the kickoff night.

Reviews, yet, were scarce. Basquiat's push-me-pull-you relationship with the art establishment was becoming evident: the dealer he wanted, Leo Castelli, rejected him every bit also troublesome; there was prejudice against him for his youth, for having first worked as a graffiti artist, for being untrained, and for being black. His piece of work was represented every bit instinctive, as opposed to intellectual, though he was well versed in art history; some held the patronising idea that he didn't know what he was doing.

Racism also had an everyday affect: he would leave successful opening parties and find it impossible to get a cab. Herb Schorr would give him lifts to brand his life easier (they would joke that he should wear a peaked cap and exist Basquiat'south commuter). George Condo, an artist on the rise at the same time, recalls going to a restaurant with him in LA and not being allowed in. "I said: 'Practise you know who this is? This is Jean-Michel Basquiat, the near of import painter of our fourth dimension.' The guy said, 'He's non coming in. We don't allow his kind in here.'" Brook Bartlett remembers a trip to Europe in 1982 during which a rich Zurich socialite intimated that she, an 18-yr-sometime white adult female, would be a civilising influence on Basquiat, who was four years older and already established. No wonder race became more prominent in his piece of work: in his 2nd LA Gagosian show, in 1983, Basquiat showed paintings such as Untitled (Saccharide Ray Robinson), Hollywood Africans, Horn Players and Optics and Eggs, featuring black musicians, actors and sportsmen.

Drugs, too, were effectually more and more. "Anybody in the East Hamlet and in the arts globe in the 80s did drugs. Wall Street did drugs, anybody did drugs," says Mallouk. Merely later on Mallouk and Basquiat carve up upward in 1983, Basquiat got increasingly into heroin. "He was sniffing it, smoking it and injecting it," says Mallouk. "There were some models that he was hanging out with that were doing it and that'south how he got into it." He became unreliable, travelling to Nippon on a whim, instead of going to Italy, where he had a show. Simply then, his focus was constantly diverted. Everyone wanted him. He was moving into a different earth: his former friends withal saw him, but intermittently.

During 1984 and 1985, Basquiat's star shot higher and higher. At that place was a lot of travel, a lot of attending. He was featured on the forepart cover of the New York Times Magazine in a arrange with his feet bare. The Warhol manor rented him an even bigger identify, a loft on Not bad Jones Street large plenty for him to utilize every bit a studio as well as a flat, and in 1985 Basquiat and Warhol had a show of paintings that they'd produced jointly. Though the poster for the testify has later been constantly reworked and sampled (even Iggy Azalea used it on the embrace of her 2011 mixtape Ignorant), at the fourth dimension, the show was not a success. 1 critic called Basquiat Warhol's "mascot". Tamra Davis says this was difficult for Basquiat.

"He really idea he was finally going to be appreciated," she says. "And instead they tore the show autonomously and said these horrible things about him and Andy and their human relationship. He got really sad, and from then on it was hard to encounter a comeback. Anybody that y'all talked to that saw him around that time, he got more and more paranoid, his dread went deeper and deeper."

And gradually, gradually his heroin use was communicable up with him. Alhough he was greatly inspired by a trip to Abidjan, Ivory Coast, and though he had shows all over the earth – Tokyo, New York, Atlanta, Hanover, Paris – it became known among his friends that he was struggling. Mallouk would become over to his Corking Jones loft. "I would beg him to get assist and he just couldn't do it," she says. "He threw the Idiot box at me. People would stop me on the street, saying Jean-Michel is in a really bad way, he has spots all over his face, he looks really out of it, you need to go and help him… Information technology was pretty common knowledge that he was not well."

In Feb 1987, Andy Warhol died at the historic period of 58. Basquiat became increasingly reclusive, though he still created piece of work for shows, and made plans, in early 1988, to revisit Cote d'ivoire to go to a Senufo village. He began to talk about doing something other than fine art: writing perhaps, or music, or setting up a tequila business in Hawaii. In 1988, he went to Hawaii to get clean: Davis saw him in LA subsequently. "He was sober, he was gonna do better, information technology was like LA had a fleck of Shangri-La near it for him." Merely his visit was foreign: he brought random people to dinner, people he'd just met at the airport, and he was unnaturally upbeat, too happy. It fabricated her afraid.

In 1988, Anthony Haden-Guest wrote an article for Vanity Off-white that describes in item Basquiat's last nighttime: 12 August 1988. In New York, he did drugs during the mean solar day, and was dragged out to a Bryan Ferry aftershow party at banking concern-turned-club MK by his girlfriend, Kelly Inman, and some other friend. He left quickly, with his pal Kevin Bray. They went dorsum to the Great Jones loft, but Basquiat was nodding. Bray wrote him a annotation. "I DON'T WANT TO Sit HERE AND WATCH YOU Dice," it said. Bray read it out to Basquiat, and left.

The side by side solar day, Inman went to the apartment at v.30pm. Jean-Michel Basquiat was dead.

It was a sad cease to a rocket-flight life. And the subsequent fight between Basquiat's estate and diverse dealers over pieces of his work was not pretty. Collectors sued for paintings bought just never received. Dealers claimed they owned works; the estate said they'd stolen them. There were too many Basquiat pieces knocking around on the market (500-600 canvasses, according to one expert): the estate would only ostend the provenance of a few. And then the taxman came knocking: Basquiat hadn't paid taxes for three years before his death.

But the years have softened or resolved the arguments, and the work has had a life of its ain. Though most of his virtually important art is owned past collectors, who keep it hidden abroad, it keeps seeping out, as if drawn to its public. And we desire his piece of work, it appears. Not only are institutions finally coming around to his genius, but his work can exist seen on T-shirts, on sneakers (Reebok did a Basquiat range), on the artillery of hip-hop artists. But samples, brusk clips taken out of context, snippets and hints of the total, heed-whirling Basquiat experience. "He questions things and he references things he wants yous to pay attention to," says Davis. "His paintings were meant to be seen by as many people as possible. They're similar movies or music, not simply for 1 person lonely."

His art is irrevocably intertwined with his life: his charisma and bulldoze, his race, his talent and pitiful demise. But it is bigger than that. Similar the best art, it needs the world and the globe needs it. And if you stand in front of a Basquiat and expect, it sings its ain song, simply to you lot.

Basquiat: Boom for Existent is at the Barbican, London EC2, from 21 September until 28 January 2018

Basquiat, every bit remembered past his friends

Michael Holman, musician and film-maker

Basquiat was born fully realised. And if anything, that is the osculation of death: y'all're gonna burn brightly and burn fast. If you impressed him, if he complimented you, y'all simply felt yous'd been blest by a saint, it was a very emotionally and spiritually profound experience. That's one of the ways to calibrate his otherworldliness. Because he would never compliment you if he didn't believe it to his cadre.

Nosotros all went out [almost] every night, till iv in the morning. Information technology was and so important. Not just did we exit and blow off steam, and meet people, have sexual activity in the bath, get high, all that stuff that you practice in clubs. But within the clubs the scene besides creatively happened … all kinds of happenings, performances, art shows … Social club 57 and Mudd Club, they fed us and they directed us and guided usa, brought u.s. together with crucial people, in a way that going to openings or concerts just didn't practice. It created a community that supported each other. It was a special fourth dimension. With [our ring] Greyness, I taped a microphone to the head of a snare drum, face up down, and fastened masking tape to the drum, then pulled the masking tape off and allowed that to exist a sound. Jean would loosen the strings on an electrical guitar, then run a metal file beyond the strings.

In 1982, two years after Jean left Gray, I'd become an avant garde motion-picture show-maker. I had this cablevision TV show, and I asked him to practise an interview. He fabricated it articulate to me, without saying anything, that I wouldn't be able to practice this interview if I didn't get high with him. He was doing base, similar a high-end form of scissure. I'd never done it before and, male child, I've never done it since. I could barely keep my focus. I could barely cease shaking, but it barely affected him. He had such a high tolerance.

He was a sensationalist. He pushed the boundaries of any kind of sensation, anything that would set off his endorphins, his nerve endings, his brain cells. He was later the sensation of something special and brilliant and different and electric and massive. Would he have been good at centre age? Well, function of middle historic period is the struggle of coming to this place in which yous know you've plateaued in some ways. When we pass that hump and kickoff going downwardly the other way, we are living and dying at the same time. I don't think he wanted to become there.

Lenore and Herb Schorr, major New York collectors, and the first to recognise and back up Basquiat

Lenore: We were very excited by the first painting we saw by him. This is not a common reaction, nosotros've found, even now! He'southward a very hard creative person for many, many people. Just we just felt he was a wonderful, brilliant artist, very, very early.

Herb: The artists understood him – some of them. They were at that place first, forth with a few professionals. Basically, he had his collector base, but they weren't knocking downward the doors for them as they are today. There was not this hysteria. Actually, nothing changes. We're simply finishing reading a volume called The Portrait of Dr Gachet by Cynthia Saltzman, which is about a Van Gogh painting, and a lot of information technology is the same story equally Basquiat. Information technology takes 20 years later on his death earlier a Van Gogh enters a museum. Anything which breaks new ground takes a while for people to take hold of upward to.

Lenore: Jean was very smart and he knew his art history. Modernism, Picasso, right upwards to the present and Jean knew it all. And so we actually had a nice rapport. I could see it in his work, Picasso, Rauschenberg, they were all important influences, he had absorbed their work. It was beautifully rendered, remade in his language, with his message, with New York at the time, his personal feelings.

Herb: We didn't see him in a drugged state, well mayhap once, he seemed a footling angry, he wasn't the same person. He would call and maybe he needed more money. Once, he called united states of america up early in the forenoon and we lived in the suburbs, you know, and he said, "I need money, I accept a painting for you lot." Merely he didn't plough up past the end of the mean solar day …

Lenore: It'south so sad, he tried to get off it. Andy Warhol tried hard with him, they would exercise together.

Herb: We have practiced memories of him. One time he said he wanted to come up and have a white homo's charcoal-broil.

Lenore: We expected him around iii and he shows up at eight, with friends. It was quite a party, there was skinny-dipping – not me! – I had the kids hither and at that place was a picayune pot beingness smoked, I could aroma information technology, and we were like, Nosotros're gonna be disrepair! Information technology was a great, fun evening.

Suzanne Mallouk, partner, 1981-1983, and lifelong friend

We immediately had this feeling of kindred spirits. We were the aforementioned age, I left home at 15, then did he. Nosotros were both first generation from immigrant families – my father was Palestinian, his father was Haitian. Both of united states didn't fit into any racial or indigenous group. Both of u.s. suffered racism. We both had old-world fathers who used corporal penalization. My female parent is English, from Bolton. His stepmother was English. Information technology was very interesting, the common histories nosotros had. Authoritarian fathers that saw European women equally a prize. And I remember it actually shaped Jean-Michel's experience. He was intelligent plenty to resent that European women were somehow valued more, he saw the racism in that, notwithstanding near of his girlfriends were white. He was conflicted about it; he discussed it with me.

I hated that I had a job and he didn't. I was an artist, also – how dare he make me work every bit a waitress and live off me! Frequently I would come habitation and he would accept money out of my pocketbook to purchase drugs. We would take terrible fights. He would say, "I promise I'll await after you when I'm famous, please only allow me do my art, I'yard going to be famous very soon." Merely I didn't keep anything, then I didn't get anything. He didn't like me keeping things, he would almost be jealous of his ain artwork. He would say, "Why do yous want to keep something of mine when you have me?" Somewhen, he gave me the bulletin that really I could no longer be an artist. He was the only artist in the family and I had to expect after him. It was kind of misogynist.

It wasn't that he only saw Andy [Warhol] every bit a father figure, he also really had a amour with him. Ofttimes when I was with the two of them together, information technology didn't feel like I was there with Jean; information technology felt like I was there with two homosexual lovers. He once joked with me that he had had sex with Andy, but I don't know if it was a joke. Jean had a history of being bisexual, but Warhol was asexual, then I don't know. People misunderstand the human relationship if they merely think Andy was helping Jean. Jean was already he was highly established, he was already famous or Andy would non take been interested in him. I call back Andy needed new life breathed into his career; I call back the two of them needed each other.

2 weeks before his death, I was living with a new swain in my niggling East Hamlet hovel. Jean rang the buzzer in the middle of the night and we both got upward, and said "Who is it?" "Jean-Michel, Jean-Michel, is Suzanne there?" I buzzed him in simply he never came up. I ran down the stairs to expect for him, only he'd gone, and ii weeks after he was dead. My heart was broken when I ran downwardly the stairs and he was gone. Because I never stopped loving him. I still feel love for him and he's been dead for over xxx years.

You're going to call up I'm mad, but I have dreams, and in the dreams Jean-Michel is ageing. It'southward as though he'due south living in a parallel universe. And often he's bellyaching that I'm at that place, he's like, "Don't tell anyone I'yard hither Suzanne. Don't tell anyone I faked my death, and peculiarly don't tell the New York Times!" He'southward but living a really simple life, in the swamplands of Florida and he sells crocodile eggs. He has this hippy married woman and nearly eight little dreadlocked children. I like it.

George Condo, artist

Jean-Michel was the showtime person I had e'er met from New York City. We were both in art punk bands – he was in Gray and I was in Girls. Our first gig was at Tier 3, a society in Tribeca, in 1979, and they were opening for us. Then I saw Jean at the soundcheck, and we started talking nigh electronic music from the tardily 50s. I had no thought he was an artist, nor did he know I was, we simply were mutual admirers of Davidovsky and Cage.

After on the same evening at the Mudd Guild, nosotros both started talking about fine art and he told me he was in a bear witness, so I went to the opening and was blown away by the paintings. In a fashion he persuaded me to motility to New York. At that moment, I knew it was fourth dimension to leave Boston for adept.So at the end of December I left. I can think vividly thinking, "It's day i of the 80s, how keen, and I'k in New York. This is where I live now."

The scene in New York was turbulent, simply wild and exciting, unsafe and demanding. Information technology seemed like you had to go a famous creative person by the fourth dimension you were 24 or you lot were finished. The pressure was extremely intense. Music was an enormous influence on both of us. Rap had come in and replaced the jazz scene to a degree; artists were using words to execute lines and phrases that normally would have been shouted out by people similar Miles Davis or Eric Dolphy with their instruments. Each of us had a number of friends who were rappers and originators of the new movement that led to hip-hop. But he came to run across me in Paris in 85 and I showed him this VHS of Miles playing So What with his original quintet and that immediately set him off to do an amazing cartoon with trumpets and the words "whole tone and hole tone" all over it. Simply someone stole information technology.

I was heartbroken when he died. I could see it coming, in his piece of work and in his life, just I hoped information technology was just another insane way of him pushing the envelope to the extreme. The last time I saw him was at [the eating house] Indochine; he told me, "I'chiliad all washed upward in this town … nobody will show my work … nobody." It was a few weeks before he died., Only Bruno Bischofberger, his long-fourth dimension gallerist, was still behind him. The pranks, the excessive junk addiction, the sultry indifference had turned anybody off. He said the only guy left willing to show him was Vrej Baghoomian. I said, "Look a minute – that's the guy who's showing me! Even when I tried to tell him not to." We both cracked up and concluded up walking up to Times Square simply lamenting and singing out our blues in the streets. I walked him all over boondocks thinking I would see him once more soon. But I never did.

Brook Bartlett, artist, was aged 16, when she met Basquiat; he became a friend and encouraged her career

Whenever I ran into him, he was ever like, "Are you lot working?" He was like a mom or something, "What are yous doing with your life?" I was making music at the fourth dimension and we would fight virtually that a lot. He would say, "I did my thing with music – you're basically a slave, especially as a black man, there's no respect. If I become into the music industry, I'chiliad only gonna be some other nigger, that's how it's gonna be. But as a painter, my colleagues are Picasso, Rauschenberg." He was very proud to be black and very sensitive virtually it.

What happened to us was [all about] coin and race. He said, "I take to go to St Moritz to run across my dealer, he'south kind of a shark only he's a good shark. Come with me, information technology's your 18th birthday, I hate leaving New York, I've never been to Europe."

Then we met Bruno [Bischofberger, Basquiat'due south Swiss dealer]. We took a private jet over the Alps, went to this dinner of Count so-and-so. It was the Iran hostage crisis at the fourth dimension, [there was] a blockade. And these people had decided to smuggle caviar out of Iran. There were salad bowls filled with Iranian caviar and people put ¼ litre-sized amounts of caviar on their baked potatoes while doing coke.

We ended up in a conversation with one of the guys doing the coke and [he] looked at me, merely turning xviii that 24-hour interval, a girl who had never shown any demonstrably corking work, and said, "You will be important for his work, y'all must testify him the mode, y'all will exist instrumental…" basically talking as though I should be taming this savage. And I was just like, this party is revolting, I wanna go home.

On the way back on the aeroplane, he was nervous, he drank a lot and he was held up for about two hours in customs. When he got out he but said that they questioned that he could wing in first class every bit a black man with dreadlocks. We kept walking and this blackness janitor, pushing a broom, like from a film, says to him, "What they become you for, blood brother?" And [Basquiat] turned round and said to him, "I'thou not your fucking brother." And kept walking. This was the guy who would give $100 bills to any Bowery bum; any brother that talked to him he wanted to talk to them. That bankrupt my heart.

Thanks to Toby Amies and Tom Wilton. This article was amended on 4 September 2022 to correct the publication engagement of an Anthony Haden-Guest article.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/sep/03/jean-michel-basquiat-retrospective-barbican

0 Response to "Who Said That Art Dies When It Is Bought"

Post a Comment